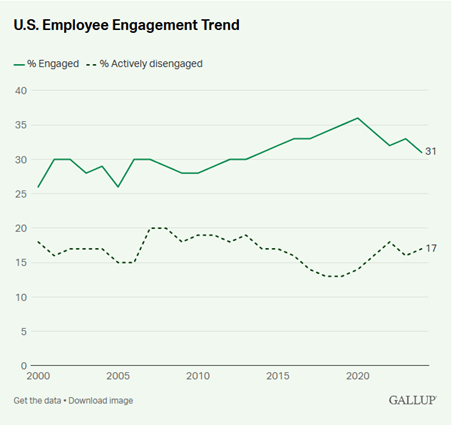

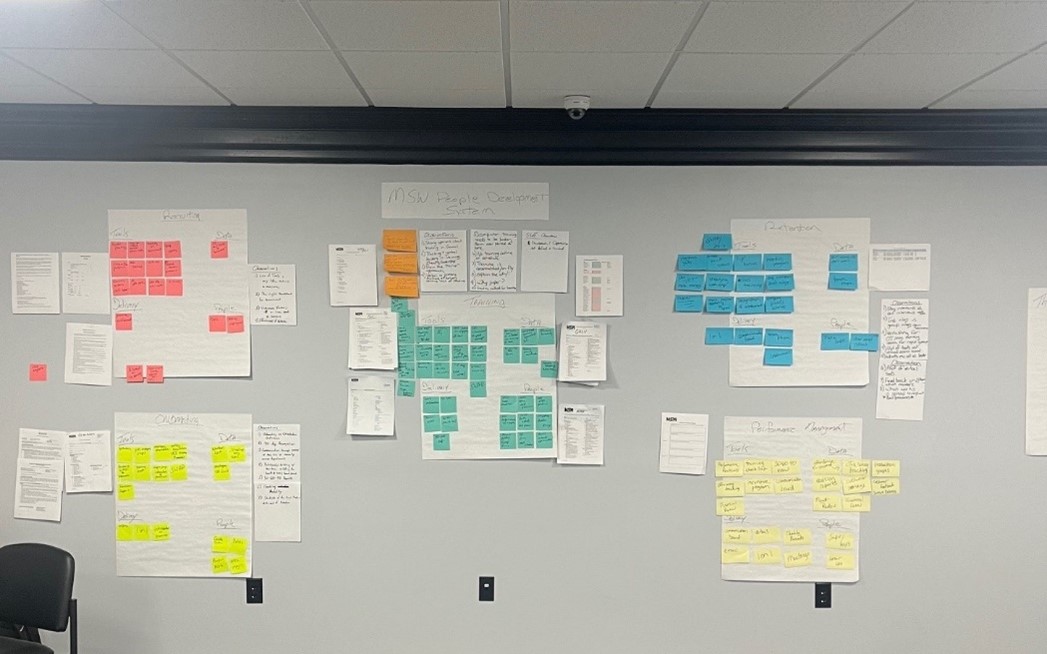

For over a quarter of a century employee engagement has been dismal. Difficulty in defining the concept has had a lot to do with this stagnation. However, a shared vision of a truly engaged workplace by all stakeholders is possible with an attentive people development system. A PDS intent upon moving the needle on this stubborn but important metric.

When the phrase appears, employee engagement generally implies that an individual has a deep level of commitment, a strong willingness to be involved, or a high degree of dedication to being a part of the team and excelling at their work. The word excitement often shows up in the definition, sometimes the word motivation, and happiness might also appear.

Some explanations seem to border on the concept of achieving a state of mental flow, suggesting that engagement is being fully absorbed by and enthusiastic about the job. Some days, yeah. Some days, no. Several people that I’ve worked with in the past who were very much bought into the success of the company could seldom be described in these terms. Nevertheless, they understood their connection and responsibility to the team, and they did, on a regular basis, contribute a great deal.

It’s a complicated concept; one that has changed over the years. Tony Martignetti and Moe Carrick, business leaders and authors, compellingly argue that employee engagement is being replaced by a sense of employee connectedness. Pointing out that the move toward connectedness has been driven by social and cultural forces that have obvious impacts in the workplace.

Along those lines, I prefer to think of employee engagement as a mutually beneficial harmony reached when both employer and employee recognize and accept their responsibility for the success and well-being of the other. It takes all parties to achieve this harmony, and it takes a responsive PDS to promote and protect it.

A Shared Understanding.

Since all stakeholders have a vested interest in this, it seems like a good idea to start by understanding employee engagement very clearly. And though it sounds simplistic, getting all PDS stakeholders on the same page is a good first step in building stronger allegiances.

It is talked about so much in certain circles that it can lead to assumptions that everyone knows what engagement is and how it matters, which is obviously not the case. Getting everyone’s mental models of this vital connection out in the open and agreeing upon a unifying model can reduce misunderstandings and misinterpretations of the concept.

Leaders of organizations, just like individual workers, have the right to think about engagement what they will and to have certain expectations about what it takes to achieve this state of harmony. There may be very little distance between the two ideals, or there could be a chasm. Alignment of expectations and agreement around everyone’s responsibilities could mean the difference between dismal performance for another quarter century and levels of engagement that are truly beneficial for all.

How Far Apart are We?

One of the primary roles of the PDS is culture building. An engaging culture connects people, shares openly, clarifies goals, promotes learning, and ensures that stakeholders share responsibility for outcomes.

An optimized PDS helps create space for dialog and allows the whole team to debate the definition of engagement and agree on ways to improve it. This falls easily under the training and development function of the system.

Start by creating small cross functional teams and share the data – turnover, average tenure, survey results, etc. Let the team know how these numbers impact both the organization and every individual within it. Then ask the teams to help improve the numbers. Everyone benefits when these indicators improve and self-interest is a powerful motivator.

Part of the retention efforts of the PDS should be to bring senior leaders into community with frontline workers through one-on-one coffee breaks, lunches, or small group brainstorming sessions. These are perfect times to bring up the topic of engagement. Ask questions about engagement, extend the dialog created in the cross functional groups. Discuss the roles that each stakeholder plays and then help them play those roles well.

These interactions are also great opportunities to further explain how being engaged is in everyone’s best interest. Thanks to the proverbial grapevine, these conversations will find their way back to the entire team. Done well, this can feed into other positive conversations, helping to drive higher levels of commitment.

Of course, this means that the leaders must be educated on those impacts and trained in having these coaching/development conversations. Another job for the optimized PDS! To be effective, leaders must understand how important employee engagement really is and how they impact it.

Measure it…But Differently.

Employee engagement is usually measured via a survey asking people about their state of mind at a particular time. Which can skew the results dramatically, depending upon moods, circumstances, and other life situations.

Instead, look for and measure individual behaviors that tend to be driven by a higher level of buy-in or consensus. These might include:

- Number of teams/groups individuals have joined,

- Number of requests individuals make for development opportunities,

- Levels of development attained (individual development plans are great for tracking this!),

- Number of ideas generated per individual,

- Involvement in and contributions to events (improvement events, community-facing events, peer support events, etc.),

- Relationships developed (social connections with co-workers, coaching, etc.),

- Willingness to be part of initiatives,

- Changes in attendance patterns,

- Personalization of workspace.

Keep doing engagement surveys, one on one encounters, and peer evaluations to assess the harmony. Even better, be creative in identifying other more meaningful metrics, realizing that being engaged influences several behavioral and personal performance indicators. Share these measures liberally with the team, encouraging them to value these outcomes.

Old Systems Will Struggle.

According to Martignetti and Carrick, “To build connected organizations, leaders must shift from driving engagement to designing relational ecosystems and from motivating individuals to strengthening networks.” Here’s a pressing question; can the organization’s internal people development system support this shift in thinking?

Look more closely at the system level for opportunities that can move the conversation in the right direction. Systems thinking is one of the three guiding principles of the Optimized People Development System framework because the PDS is a dynamic system and difficult to see. It is also the most important organizational system for fostering connections and relationships.

Employee engagement has languished far too long. Establishing a shared definition and innovative measures of employee commitment and their wellbeing can help move the numbers in the right direction. An optimized PDS, one that fosters a new mindset around engagement and connection can help keep that movement going.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay